According to El Mundo, microbiologist Patricia Bernal, winner of a Leonardo grant from the FBBVA, is researching a technique to eliminate the bacterium ‘X. fastidiosa’, which causes the disease that kills olive trees and other crops, using another bacterium that is harmless to nature and the health of people and animals.

The olive tree is much more than just a tree in Mediterranean countries, and not only because of its great economic importance. It is a cultural symbol in many regions of Spain, Italy, Greece or Portugal under which a threat called Xylella fastidiosa looms. It is a bacterium from America that was first detected in Europe eight years ago.

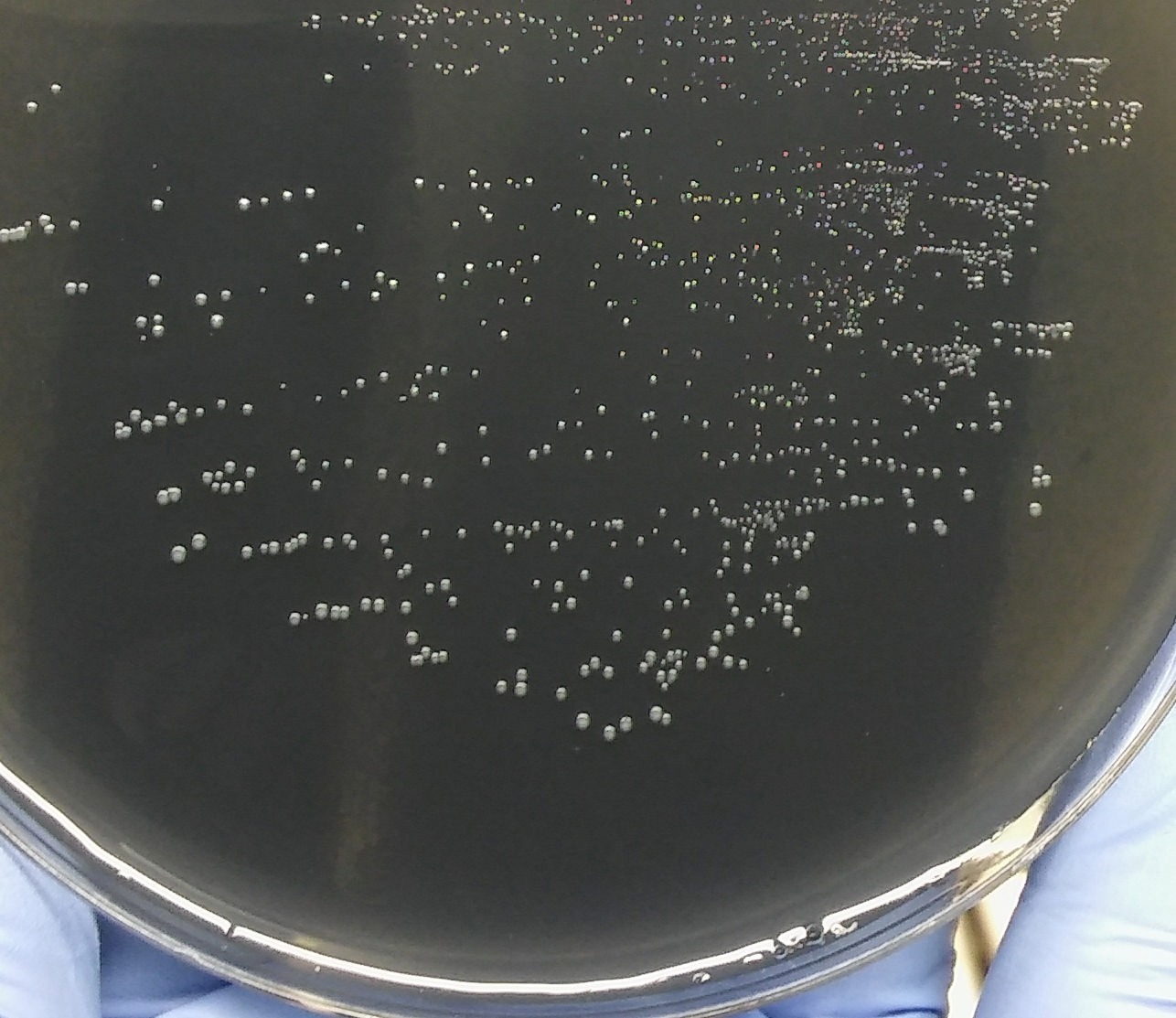

It is transmitted by sucking insects when they bite a tree to feed on its sap, and once it settles in the tree, it clogs the vessels through which the sap circulates from the roots to the leaves, weakening the tree and even causing its death. Because of its seriousness, the disease it inflicts on the trees has been called olive tree Ebola, a term that scientists do not generally like, as it is neither a virus nor does it affect people or animals. Moreover, this bacterium not only infects olive trees, it is also destructive for vineyards, almond trees, citrus trees, coffee trees and stone fruit trees such as plum and peach trees.

«As a micro-organism, Xylella fastidiosa is nothing like Ebola from a scientific point of view, its way of acting is very different. It is a bacterium that causes a disease in plantations of interest to humans because they are economically important, both crops and ornamental plants», summarises microbiologist Patricia Bernal Guzmán (Seville, 1977), who has launched a new research project to combat this pathogen that causes this disease in crops and for which there is currently no cure.

To try to develop a treatment to put an end to it, Patricia Bernal, who is group leader and Ramón y Cajal researcher in the Department of Microbiology at the Faculty of Biology of the University of Seville, has 40,000 euros at her disposal, which the BBVA Foundation has just awarded her through one of the 59 Leonardo grants aimed at researchers and cultural creators between 30 and 45 years of age.

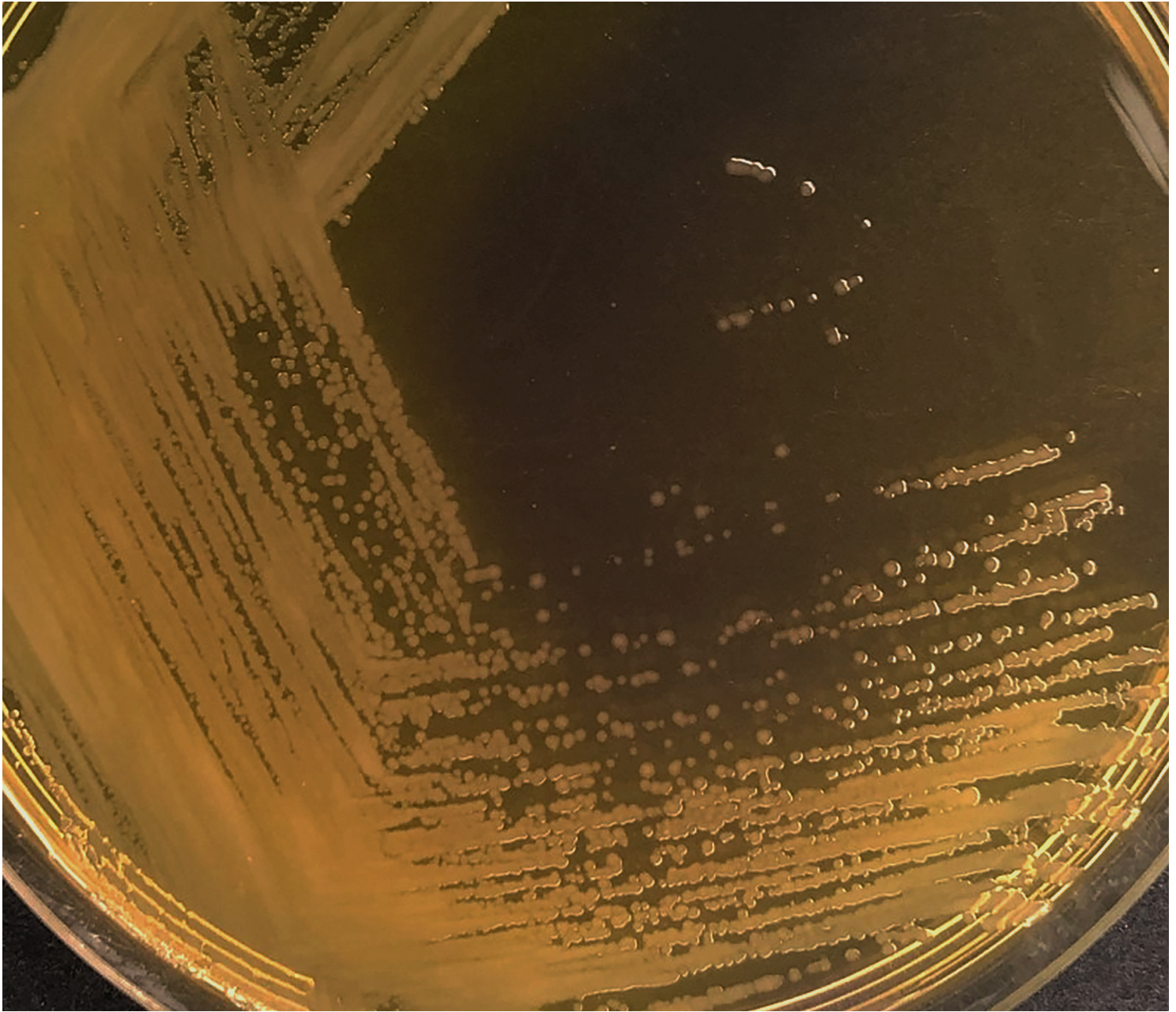

Bernal is a biocontrol specialist, which means she is an expert in keeping pathogens at bay. And basically what she is going to do in her lab is to use a bacterium that exists in nature to fight another bacterium, without using pesticides or other chemicals. «I am going to study the ability of Pseudomonas putida KT2440, which is a safe bacterium, very well studied and with a great capacity to kill plant pathogens, to fight the bacterium X. fastidiosa,» she summarises.

Their strategy is therefore based on using the toxic molecules secreted by harmless micro-organisms to fight pathogenic micro-organisms. «You have two bacteria fighting. Pseudomonas putida strain KT2440 shoots toxins at other bacteria to kill them. It has up to three different ‘weapons’ with different toxins,» says the scientist, who has already shown in previous publications that it is effective at killing other types of pathogens that infect crops such as tomatoes, beans and peas.

For example, Bernal says, it effectively kills Pseudomonas savastanoi, which causes olive tuberculosis; Pseudomonas syringae, which infects a wide range of species including tomato, bean and pea; Pectobacterium carotovorum, which rots various tubers; and Xanthomonas campestris, which infects plants such as almond, peach, cherry and plum trees.

«The advantage of biocontrol over current methods of pest control, which are mainly chemical agents such as pesticides, is that biological agents such as the bacterium Pseudomonas putida are not a threat to the environment – they do not contaminate soil or groundwater – or to the health of animals and humans, and are therefore important for sustainable agriculture,» he argues.

The name X. fastidiosa, by the way, is not because of the problems it causes in the field, but because it is difficult to grow in the laboratory, and its name, Xylella, comes from the place where it lives in the xylem of plants.

DIFFERENT STRAINS OF ‘X. FASTIDIOSA’ STRAINS

«The X. fastidiosa bacterium has been known for a long time in America, where it causes major problems in vineyards in the USA and citrus in Brazil. Different strains of the same bacterial species cause problems in different crops«, he says.

As the microbiologist reviews, the bacterium was first described in America in 1987 as the cause of Pierce’s disease in grapevines, which had been known since the 19th century. It spread throughout the Americas, from northern Canada to southern Argentina, causing multi-million dollar losses.

However, «the strain of X. fastidiosa that became most famous was the one that arrived in southern Italy, first in the Apulia region, where it was detected in 2013 and wiped out thousands of hectares of olive trees, as well as affecting 30 other host plants,» he says. In 2015, the bacterium was detected on the island of Corsica and in 2016, in the south of France, affecting mainly ornamental plants and wild species of Mediterranean scrub. In 2016 it was Spain’s turn, specifically in the Balearic Islands (Mallorca, Menorca and Ibiza), where wild olive, olive, almond and vine plants, among others, were found infected. In 2017, the first cases were detected in the Iberian Peninsula, specifically in different municipalities of Alicante, affecting mainly almond trees. In April 2018, two isolated cases were described, one in an olive tree in Madrid and another in ornamental polygala plants in a greenhouse in El Ejido in Almeria. Finally, in 2019, it was detected in Portugal, in a region close to Porto.

Afortunadamente, dice Bernal, la cepa que en Italia ha infectado al menos unas 200.000 hectáreas de terreno en las que hay en torno a 20 millones de olivos, algunos centenarios, no ha llegado todavía a España: «Se están tomando muchas medidas preventivas para evitar que la dramática situación que ha ocurrido allí se dé en nuestro país.Porque en Andalucía en particular y en España en general, dice la microbióloga, la pérdida del patrimonio que representan los olivares «tendría un valor incalculable y por ello es crucial ponerle freno al patógeno y evitar que sea introducido en zonas de nuestro país libres de la bacteria, o que se extienda desde zonas infectadas al resto de nuestro país y del mediterráneo.

Fortunately, says Bernal, the strain that in Italy has infected at least 200,000 hectares of land with around 20 million olive trees, some of them centuries old, has not yet reached Spain: «Many preventive measures are being taken to prevent the dramatic situation that has occurred there from happening in our country. Because in Andalusia in particular and in Spain in general, says the microbiologist, the loss of the heritage represented by the olive groves «would be of incalculable value and it is therefore crucial to stop the pathogen and prevent it from being introduced into areas of our country free of the bacterium, or from spreading from infected areas to the rest of our country and the Mediterranean.

As Landa points out in an e-mail, in Spain, sampling is carried out continuously throughout the year, both in fields and in greenhouses, within the framework of the Contingency Plan of the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, and the different autonomous regions are responsible for plant health. In addition, at European level there is a control (audits are carried out) to monitor the procedure and ensure that the containment measures applied by each country are adequate. «As a consequence of this intense sampling in recent years, the number of host plants where Xylella has been detected has increased. When a positive detection is made, the vegetation around the affected plant is threshed in an area of 50 metres (previously 100 metres)». The Levant and the Balearic Islands are the most affected areas.

His project will initially last 18 months, during which time different strains of Pseudomonas and Xylella will be tested in vitro in this laboratory. «For the moment we are going to do basic science, if we are successful and if we have funding later we will see how to take it to the field, possibly infiltrating the bacteria in the olive tree or in the insect, although that part is still a long way off,» says Bernal.